Authors

Archived Posts from this Category

Archived Posts from this Category

Posted byAlison Aten on 15 Jun 2019 | Tagged as: Authors, Native American

Powwow season is in full swing. Did you know that one of the most popular traditional dances was inspired by a dream given to the Ojibwe people during a global health crisis?

One hundred years ago in 1918-1919 when the global influenza pandemic killed millions worldwide, including thousands of Native Americans, a revolutionary new tradition of healing emerged in Ojibwe communities in North America: the jingle dress dance. Oral histories vary on where exactly the jingle dress first appeared, but the Mille Lacs community in Minnesota was a center of activity.

Ojibwe scholar Professor Brenda J. Child of the University of Minnesota recounts the origin story of the jingle dress dance and the significance of the dance as a powerful healing tradition and act of anti-colonialist resistance and female empowerment in her award-winning book, My Grandfather’s Knocking Sticks: Ojibwe Family Life and Labor on the Reservation (MNHS Press).

In the book she recounts:

“An Ojibwe girl became very sick. She appeared to be near death. Her father, fearing the worst, sought a vision to save her life, and this was how he learned of a unique dress and dance. The father made this dress for his daughter and asked her to dance a few springlike steps, in which one foot was never to leave the ground. Before long, she felt stronger and kept up the dance. After her recovery, she continued to dance in the special dress, and eventually she formed the first Jingle Dress Dance Society.”

Child notes that the story suggests an influenza-like illness, making is possible that the first jingle dress dancer suffered from the widespread epidemic of Spanish flu during the World War I era. She writes:

“Although a man conceived the Jingle Dress Dance after receiving a vision, women were responsible for its proliferation … Once the influenza epidemic struck, women applied the ceremony like a salve to fresh wounds. They designed jingle dresses, organized sodalities, and danced at tribal gatherings large and intimate, spreading a new tradition while participating in innovative rituals of healing. Special healing songs are associated with the jingle dress, and both songs and dresses possess a strong therapeutic value. Women who participate in the Jingle Dress Dance and wear these special dresses do so to ensure the health and well-being of an individual, a family, or even the broader tribal community.”

Her book also highlights the design and construction of the jingle dress and how the dance has spread throughout and beyond Ojibwe Country. Today jingle dress is a popular dance form on the competitive powwow circuit and is performed by Native women with a variety of tribal affiliations.

Child also recently curated an exhibit on the history of the jingle dress to marks its 100th anniversary at the Mille Lacs Indian Museum and Trading Post in Onamia. Featuring jingle dresses from a variety of eras, the exhibit “Ziibaaska’ iganagooday: The Jingle Dress at 100” will be on display through Oct. 31, 2020.

Brenda J. Child (Red Lake Ojibwe) is Northrop professor of American studies and American Indian studies at the University of Minnesota. She is the author of the critically acclaimed children’s picture book, Bowwow Powwow illustrated by Ojibwe artist, Jonathan Thunder which features a jingle dress dancer. She has been featured in Indian Country Today, Native America Calling, Minnesota Public Radio, and has lectured at the National Museum of the American Indian. We asked her a few more questions about the history and significance of the jingle dress dance.

Q & A with Brenda J. Child

How do modern jingle dresses differ from dresses a hundred years ago? How were and are they made?

We organized an exhibit at the Mille Lacs Indian Museum and Trading Post in Minnesota to show the evolution of the jingle dress over the past century. Dresses from the 1920s and 1930s resembled flapper dress styles of the day, and the jingles are made from a variety of materials– chewing tobacco lids, baking powder cans, and Prince Albert tobacco cans. Today’s dresses tend to be more elaborate than those of the early 20th century, but they are all very beautiful.

Can you talk a bit about the extensive photographic record of jingle dresses in the Great Lakes?

I first realized that the Jingle Dress Dance Tradition emerged during the flu epidemic when I was unable to find a photograph in the US or Canada of the Jingle Dress prior to circa 1920. For a historian, that told me something very big had recently happened. I eventually put the jingle dress stories we tell in our communities together with my understanding of the terrible impact of the flu epidemic on Native communities of the US and Canada.

How did Ojibwe women use the therapeutic power of the jingle dress?

They used it to heal their communities. This particular epidemic killed people in the prime of their lives, young adults. It killed more people than World War I.

The jingle dress tradition emerged around the same time as the Dance Order from Washington arrived in 1921. What was that order and did it affect the dance?

The Jingle Dress at 100 exhibit tries to answer two questions. First, why is it the the hundredth anniversary of the tradition? This is where I try to explain the history of the global epidemic. Second, I also consider how the jingle dress has been in the past, and remains today, a radical tradition. It emerged in the context of a global epidemic of influenza one hundred years ago, but the tradition is still with us today because it has been embraced not just by Ojibwe people, but Dakotas, and women from many tribes. It emerged in an era when ritualistic dance was banned in the US. Many of the protesters at Standing Rock were jingle dress dancers, and so women have been politically empowered by the tradition as well. It remains a vibrant and modern tradition, even though it is a century old.

Posted byAlison Aten on 08 Mar 2018 | Tagged as: Authors, Interview, MHS press, Nature/Enviroment

Join us next Wednesday, March 14, at 7:00 pm at Magers & Quinn Bookstore to celebrate the publication of Wild and Rare: Tracking Endangered Species in the Upper Midwest by Adam Regn Arvidson. Here he tells us what inspired him to write the book and the adventures he went on and the interesting people he met while researching it.

What is your connection to Minnesota and its landscapes?

I’m originally from the Chicago area, but I’ve lived here now for twenty years. What I loved right away when I moved here—and what I still love about Minnesota—is the incredible variety of landscapes. We are the only state in the US that has three major biomes (prairie, deciduous forest, and mixed conifer forest) without significant elevation change. Those three biomes are as different from each other as jungles, deserts, and coral reefs are. And they all exist right here, within a couple hours’ drive of the Twin Cities.

As someone who grew up ranging far afield from suburban Chicago for outdoor adventures, that landscape diversity is exciting. As a landscape architect who has worked on and written about projects all over the country, I find the Minnesota landscape to be an ever-stimulating source of ideas and inspiration. Edward Abbey writes about how everyone has their ideal home landscape, even if it wasn’t the one they were born into. I feel that way about Minnesota and the upper Midwest. I feel equally at home in the grasslands, the oak woods, and the northern forests. I also love being able to move freely—and quickly—between them.

Wild and Rare is both very focused on our region and also wide-ranging in terms of the species you cover. What made you want to tackle your subject this way?

I am a great lover of lists. I am most definitely a National Parks and State Parks Passport holder. The origin of the book goes way back to around nine years ago, when I visited the International Wolf Center and heard wolves howl for the first time. That moment—which appears in the introduction to the book—was followed by a trip to an Ely food-and-drink establishment, where I wrote the first draft of the description of the howling. But more importantly, I got curious about what other plants and animals might be on the endangered species list. With smartphone in one hand and Minnesota brew in the other, I learned of the (then) twelve listed species. I saw one I recognized and had a deep affinity for—the dwarf trout lily—and many I didn’t. I realized right away that, put together, that list described every landscape in Minnesota, almost every type of living thing, and covered the entire geography of the state.

My goal has always been to describe the beauty and complexity of this state and its neighbors. The species are a gateway to that. The endangered species list, seen item by item, shows off the whole. And along the way I learned more about my adopted home place than I ever thought possible.

You have been out in the field a lot with scientists in researching this book. What are some of your favorite stories from those trips?

Perhaps the most unexpected trip was when I joined Joel Olfelt and his Leedy’s roseroot research team. I met them in a farm field in southeastern Minnesota, and Joel unpacked an aluminum extension ladder. A ladder to catalog plants? We descended steeply (carrying the ladder) into a river gorge with sheer cliffs on both sides and propped the ladder against the rock. Climbing the ladder was a surreal and memorable experience. It was hard to imagine this was a Minnesota landscape. The cliff was dripping with moisture and the river rushed below me. And there on the cliffside were these little plants, each with a metal tag. Joel has spent around two decades following the life stories of these plants—and I was wondering how anyone ever found them in the first place.

Another memorable story is when I tracked lynx with Dan Ryan of the US Forest Service. I really didn’t know what I was in for, and I spent a lot of time foundering in the deep snow. I sometimes fancy myself a rugged outdoorsman, but Dan is the real deal. He let me follow tracks, but I had to keep asking him to verify what I was seeing. He cruised through the thickets, while I repeatedly fell in the snow and got tangled in the brush. I can’t imagine doing this work in twenty-below weather or even deeper snow—both of which Dan regularly experiences. He, like pretty much every scientist I worked with on this book, was patient and generous. He may have been chuckling at this city kid under his breath, but he didn’t show it.

How do you turn all that research into chapters that both educate and entertain?

One of my former teachers called me a “binge writer.” I can’t start writing a chapter until all my research is done. By the time I sit down to write, I have already been in the field multiple times, scoured the online Federal Register documents, read books, and done phone interviews. Then I sit down and write a chapter, usually in about two days of solid, nose-to-the-grindstone hunting-and-pecking, most often in coffee shops (I suppose I should have credited my regular haunts in the book’s acknowledgments).

Once the draft is done, I print it out, cut it apart, and start rearranging the sections to make them flow better. I’ve most often done this while holed up for a weekend in a Minnesota State Park camper cabin, papers strewn across the floor, three chapters a day: morning, afternoon, evening. Once I have an order I like, I go back to my tablet and re-arrange the digital version, polishing transitions as I go. This task often reveals where I have research gaps, so I do another round of calls, searches, and readings.

The great writer Barry Lopez, in a writing class I was once lucky enough to take, talked about the “genius of the first draft.” He is extremely careful about the editing he does, and will often work on an essay for months or years without changing much. In my case, the re-arrangement significantly changes how the chapter flows, but the base text doesn’t change much from that first binge-writing session.

Lopez also talked about the positions of the writer and the reader relative to the story. He feels many writers put themselves up front, potentially in the way of the reader. He prefers to begin beside the reader, and then gradually move the writer into the background behind the reader. This way, the reader has a full view of the story, with the writer sort of whispering in the reader’s ear. I can’t guarantee my book does this, but it’s what I strive for.

What are the main threats facing endangered species in the Midwest?

Of course it varies by species. But if I had to boil it down, I think there is a very simple big three: water quality, habitat loss, and climate change. Poor water quality and increased storm runoff has significantly hurt freshwater mussels, and is likely affecting the dwarf trout lily and the Topeka shiner. Habitat loss is a major one. Without prairie—of which we have lost more than 99 percent in this country—there will be no prairie fringed orchids, no bush clover, likely no Topekas, and definitely no prairie butterflies. Loss of forest habitat affects the wolf and lynx. Beachfront development gets the plover.

Climate change is a little more esoteric. It’s definitely happening, and in some cases the effects are becoming well known. But exactly how it will affect different landscapes is still an open question. And it could be argued that species like the lynx will simply migrate north and be perfectly happy in Canada. But even if plants could gradually migrate north, they likely can’t do it quickly enough and there might not be suitable soils and moisture in their new temperature range.

One message in all this is hopeful. The Clean Water Act of 1972 fundamentally changed the way we treat urban and rural waterways. There is still work to do (especially with agricultural runoff and road salt), but rivers and lakes, overall, are cleaner than they were before that act. That’s why Mike Davis is reintroducing mussels to the Mississippi.

How has the writing of this book, over the course of nine years, changed you?

For starters it made me into a birder. I didn’t know the difference between a red-tailed hawk and a Cooper’s hawk. But then I went to Texas and started trying to identify shorebirds and it opened a whole new world for me. And my kids got all wrapped up in it, too (sorry, boys). We all have eBird accounts and carry binoculars when we hike. I also started cross-country skiing, after trying it in the amazing snow when I was up north tracking lynx with Dan Ryan. Now it’s one of my favorite things.

I suppose the main change has been that I enjoy this state even more. I itch to get outside, no matter the weather. I look at maps and pick out the parks I want to visit (a list-maker’s hobby).

I also find myself plagued or blessed (depending on my perspective that day) with a constant mix of fear and hope over the fate of our fellow travelers on this globe. Every species I tracked in this book has a rather horrible story of either deliberate or collateral persecution by we humans. Every one also has an uplifting story of resilience and potential—often because of the care and passion of humans. Sometimes both stories exist at the same moment in time.

For instance, I have come to believe (regardless of what the “settled science” says) that pesticides, specifically neonicotinoids, are killing bees and butterflies. Right now. Every day. But at the same time, scientists at the Minnesota Zoo are raising and releasing endangered butterflies into the wild. Will they meet the same fate as their forebears? Will they thrive and repopulate the prairies? I don’t know. And I both worry about that and get excited about that. I love this upper midwestern landscape deeply. I believe it will last forever, and I also fear it won’t.

Posted byAlison Aten on 17 Nov 2017 | Tagged as: Authors, Food, Scandinavian Studies

Patrice Johnson is a Nordic food geek and meatball historian who loves to give old Scandinavian recipes a modern spin. Her new book is Jul: Swedish American Holiday Traditions.

In exploring these holiday customs, Patrice begins with her own family’s Christmas Eve gathering, which involves a combination of culinary traditions: allspice-scented meatballs, Norwegian lefse served Swedish style (warm with butter), and the American interloper, macaroni and cheese. Just as she tracks down the meanings behind why her family celebrates as it does, she reaches into the lives and histories of other Swedish Americans with their own stories, their own versions of traditional recipes, their own joys of the season. The result is a fascinating exploration of the Swedish holiday calendar and its American translation.

Here’s her recipe for Skurna Knäckkakor or Swedish Toffee Shortbread Slices:

When I tested this recipe, I ate half of the batch before it was completely cooled. It was important to rid the house of the remaining cookies immediately so that I didn’t finish them all. These are the best cookies I’ve ever tasted. They have a dense texture with a hint of toffee. You have been warned.

¼ cup raw, unpeeled almonds

½ cup (1 stick) butter, softened

½ cup sugar

1 tablespoon light or dark corn syrup

1 ½ teaspoons vanilla extract

1 teaspoon baking powder

1 ½ cups pastry flour

¼ teaspoon salt

Preheat oven to 350 degrees and line baking sheets with parchment paper. Process nuts in food processor or use nut grater to create a medium- to fine-textured meal. Blend all ingredients together, first using electric mixer at low speed for 1 to 2 minutes and then finishing by hand to form a dough. Divide into 2 to 3 equal parts. Using hands, roll each into a log 10 to 12 inches long, place on prepared baking sheets, and flatten into a rectangle. Bake for 12 minutes. While still warm, use a dough scraper to cut each rectangle diagonally into thin slices.

MAKES 50 COOKIES

Posted byAlison Aten on 13 Apr 2017 | Tagged as: Authors, History, Immigration

Join us on Wednesday, April 19, at the American Swedish Institute to celebrate the publication of Scandinavians in the State House: How Nordic Immigrants Shaped Minnesota Politics by Klas Bergman. Klas will be joined in conversation by Tom Berg, attorney and former state legislator.

Event details here. $5 per person, reservations requested. Klas will also share his book in Duluth and Marine on St. Croix.

Why did you write this book?

Growing up in Stockholm, Sweden I read–no, devoured–the epic tales by Vilhelm Moberg about the Swedish immigrants to Minnesota. Later, I became an immigrant myself and I continue to be fascinated by immigration and immigrant stories. In this book, I managed to combine that interest with my other great interest, American politics.

It’s about how hundreds of thousands of Scandinavian immigrants in Minnesota, who started arriving in the 1850s, took part in building a new state, came to dominate the state’s politics ever since the breakthrough in 1892, and created the U.S. state that most resembles Scandinavia, both politically and culturally. This book has really been a wonderful and challenging project, full of great drama and fascinating personalities.

What surprised you the most in your research?

Well, a lot of what I learned was new to me, and it might be new to many readers, for this aspect of the Scandinavian immigrant story is not widely known. But what surprised me, in particular, was the sheer number of Scandinavian politicians, at all levels in Minnesota’s society, and how they, often very soon after their arrival in the new world, became involved in politics, voting and running for office. They assimilated quickly; they wanted to become Americans. This is, I believe, a crucial part of the history of Scandinavian immigration to Minnesota, for these Scandinavian politicians helped create today’s Minnesota.

What are the key ingredients in that political legacy?

It’s been called a moralistic political culture, shaped by the Scandinavians together with those who came before them to Minnesota from New England, the Yankees. It’s pragmatism and a feeling of community and equality, with abundant cooperative activities. The idea of helping your neighbor is important, and nothing is more important than education. Former governor Arne Carlson talks about the “common good,” combining prudence and progressivism.

Many Scandinavians also came to Minnesota for political reasons – why?

Yes, there were thousands of them, Swedes and Norwegians but, in particular, Finns. Many of them were reluctant immigrants, blacklisted in their home countries for their political and union activities and unable to find work there. They left for America to find work, to survive. I call them radicals in exile, where, in Minnesota, they often continued their political activities, published newspapers, gathered in various political groups and parties, led the strikes in the mines on the Iron Range. When the American communist party was formed in the early 1920s, over 40 percent of its members were Finns.

What were your sources for your research?

In addition to reading extensively in the existing Scandinavian immigration literature and the rich Scandinavian language press in Minnesota, I found some previously unpublished material, which was very exciting. I also traveled widely around the state and conducted a large number of interviews with politicians, scholars, journalists, and others, including former leading Scandinavian politicians such as Walter Mondale, Wendell Anderson, Arne Carlson, and Roger Moe, as well as members of the present generation of Scandinavian politicians. The interviews were an essential part of my research, and they provide an important, extra dimension to my book.

Minnesota’s population is changing. There are very few new Scandinavian immigrants. Will their political legacy survive when the new immigrants are Somalis, Hmong, and Latinos?

That is the important question I try to answer in the book. Still, today, one-third of Minnesota’s 5.4 million residents regard themselves as “Scandinavians,” so, generally, the answer is, yes, that legacy will survive because it is so firmly entrenched in Minnesota’s political culture. But one cannot say this with absolute certainty, and only time will tell.

Did the five Nordic immigrant groups play equally important roles in Minnesota politics?

No, not at all. The Danes played only a modest role in Minnesota’s policy, although there were individual exceptions; the Icelanders were relatively few, but they distinguished themselves through their important newspaper, the Minneota Mascot; and the Finns put a radical stamp on Minnesota politics as strike leaders on the Iron Range and as numerous socialist and communist party members. But it was the Norwegian immigrants, who came from a not-yet-independent Norway, who took the political lead early on among the Nordic immigrants, and Norwegian-born Knute Nelson’s election victory in 1892 resulted in a century during which all but five of the governors were Scandinavians and during which two Norwegian Americans, Hubert Humphrey and Walter Mondale, were elected vice presidents of the United States.

Who is this book for?

I think it’s for everyone who is interested in immigration and American history and politics and, in particular, Minnesota and midwestern history and politics. And at a time when immigration and refugee policy is high on the agenda the world over, the book is perhaps also a reminder of the importance of immigration and how the Scandinavians were received in Minnesota. They were welcomed, and their labor and their professional skills were needed. All this allowed them to create a new future for themselves and their families, which is why they came to Minnesota in the first place.

Posted byAlison Aten on 06 Mar 2017 | Tagged as: Asian American, Authors, Interview

Mai Neng Moua founded the Hmong literary arts journal Paj Ntaub Voice and edited the groundbreaking Bamboo Among the Oaks: Contemporary Writing by Hmong Americans. In her new memoir, The Bride Price: A Hmong Wedding Story, she shares how she struggles to reconcile two cultures: Hmong and American.

Meet Mai Neng at 6:00 p.m. on Wednesday, March 15 at Buenger Education Center, Concordia University, St. Paul for the book launch celebration.

What is the bride price and what is the difference between a bride price and a dowry?

In the Hmong culture, the bride price is money the groom’s family pays the bride’s family as part of the marriage ceremony. It acknowledges the hard work the bride’s parents have done in raising a good daughter. It offers a promise of love and security from the groom’s family. A dowry is the money and goods that the bride brings to the marriage, often including gifts the bride’s relatives give to her to start her new life.

Does the Hmong community still collect bride prices for their daughters?

In general, yes, this still happens today. This is how most Hmong marry. However, the Hmong have been in the U.S. for over 40 years, and, in that time, some Hmong have changed, and they no longer collect bride prices for their daughters.

Why did you decide to write a book about the bride price?

As a writer, I am committed to my individual story, which sheds light on the struggles of being Hmong American or what it means to be Hmong in America. I love being Hmong and yet, because I came to the U.S. when I was eight years old and I became a Christian, I struggle with separating culture or traditions from religion. I do not know or understand the deep meaning of many of the animist rituals or ceremonies. I decided to share my story so that it may stimulate conversations in the community about what it means to be Hmong. I am not telling young Hmong Americans take a stance against the bride price. I am challenging them to deeply understand who they are and why they believe what they believe. If they do not know, they should talk to their parents or elders. I am saying, know who you are and own your beliefs.

What do you think will be the reception of your memoir in the Hmong communities in the U.S. and elsewhere?

The bride price is a controversial issue. Some may appreciate the honesty of the book. Others will be angry that I am calling it a bride price, that I have not explained the full cultural context for it. The title itself may be too controversial for some. I do not pretend to be an expert on Hmong culture, traditions, or history. I do not speak for Hmong women or the Hmong community. This is a memoir, which means it’s a story told from my perspective. And that perspective is of someone who came to the U.S. when she was eight years old, grew up in the church memorizing Bible verses and singing Christian songs. Her level of understanding of Hmong culture is that of the first level of translation, that of a child’s, the literal translations only. If you read it in that context then it will make sense.

How did you go about writing your book? Did you have to do any research for it?

When my mother and I stopped talking, I started writing letters to her. I called them Letters to Niam (niam is the Hmong word for mother). Since I could not talk to my mom in real life, I talked to her through those letters. Then I started writing different vignettes, short scenes of conversations or moments at the farmer’s market. It was such a “big” story that I did not know how to piece it all together, so I just kept writing different moments. This went on for years. Finally, I put it all together and gave it to some writer friends to read. They gave me valuable feedback about what made sense or needed more work. They asked me hard questions. I went through so many drafts that I lost count. In between the different drafts, there were years when I did not look at it. Finally, I was so sick of my own story that I either wanted to be done with it so I could write something else or stop being a writer. I took a year’s leave of absence from my day job. I did not have an agent or a publisher, but I had kept in touch with the editors from Bamboo Among the Oaks. I cleaned up the manuscript and sent it to my editor along with a handful of other readers. I thought I was done, but one of my readers said, “This needs more work.” I cursed him, took a little time off, then went back to the comments of all my readers. I took them seriously. One of my readers encouraged me to interview cultural experts or elders about the bride price. “The last thing you want is for them to accuse you of not knowing what you’re talking about.” I interviewed a handful of experts, including my uncles, cultural experts or facilitators, and leaders or practitioners of animism. I also read a lot of books on Hmong culture and traditions.

You write about the toll of the bride price on you and your mother, yet many other Hmong women have gone through traditional Hmong weddings in which their parents have collected bride prices for them without objecting to the custom. Why do you think that is?

The reactions Hmong women have about the bride price are indicative of how complicated this issue is. You will find women who do not know what it is or why we do it. Some do not really care what happens, as long as they are married. Others feel that their in-laws do not “value” them as much because their parents did not ask for bride prices. Some women say, “My parents better ask for a big bride price for me!” Whatever Hmong women feel about it, the decision to collect a bride price is not theirs to make. They have no say about it. It is their parents who decide if and how much of a bride price to collect. So, Hmong women are all over the place about the bride price, because we live in America and the rules here are different. Our parents sometimes feel differently about it, too.

Your mother is a central figure in your book. In the memoir, you describe how you and your mother did not talk for over a year. What is your relationship with her now?

My mom and I are good. She loves my girls. She loves me. It took having my own kids for me to understand my mother’s deep love for me. In writing this book, it was important for me to get her take on things. There were certain factual things I wanted to make sure I got right. Besides, I had unanswered questions for her. I took the manuscript and translated many parts of it for her. I taped our conversations. Half the time she was saying, “You know what you did was wrong, right?” I just sat there and took it. Other times, I argued with her. We cried. We laughed. We loved each other.

Posted byAlison Aten on 10 Oct 2016 | Tagged as: Authors, History, Interview, Women's History

Beginning in the late 1970s, a wave of feminist organizing broke on the shores of the Twin Ports of Duluth, Minnesota, and Superior, Wisconsin. Its impact has transformed the lives of women and men in these communities and far beyond. In Making Waves: Grassroots Feminism in Duluth and Superior, historian Elizabeth Ann Bartlett chronicles the vital history of the groups and individuals who put Duluth and Superior at the forefront of pioneering and innovative feminist organizing.

We asked Beth more about her book and what made the feminist community of the Twin Ports so special.

Join us on Tuesday, October 11, at Moon Palace Books in Minneapolis as we celebrate the publication of Making Waves with Elizabeth Bartlett.

Why did you decide to write a book about the history of grassroots feminist organizations in Duluth and Superior?

In the fall of 2002, hundreds of local feminists gathered at the University of Wisconsin–Superior for “Making Women’s History Now: The State of Feminism in the Twin Ports,” a conference that brought together feminists from a variety of organizations and across generations to talk about the pressing issues facing the feminist community. In her keynote address that morning, longtime activist Tina Welsh, director of the Women’s Health Center, chronicled the early days of feminist organizing in Duluth, from the development of the first rape crisis center to the trials of establishing and sustaining an abortion clinic. In her afternoon keynote, Ellen Pence, well known for her work in the battered women’s movement, regaled the crowd with her humorous rendition of the early efforts of the battered women’s movement in Duluth to work with the criminal justice system to set up a coordinated community response to domestic violence. As Ellen began to tell her story, my friend and colleague Susana Pelayo-Woodward and I turned to each other and said, “We need to write these down!” The conference had reminded us of what we had always known—that we lived in an incredibly special and what we felt was quite a unique feminist community.

Duluth seems so remote to be such a hotbed of feminist organizing. What makes this feminist community and the organizations that developed here so special and unique?

The programs and policies developed by feminist organizations in the Twin Ports of Duluth, Minnesota, and Superior, Wisconsin, have been groundbreaking, and the sense of connection and community is inspiring. Duluth has been the home of some of the earliest, longest-lasting, and significant grassroots feminist organizations, many of which have grown to become national and international leaders in feminist activism, serving as models of feminist practice.

Perhaps the best-known examples of this are the “Duluth Model” and the “Power and Control Wheel,” a policy for and analysis of domestic abuse used widely throughout the United States and world. The Program to Aid Victims of Sexual Assault (PAVSA) and Safe Haven Shelter and Resource Center were among the first rape crisis centers and domestic abuse shelters in the country. Mending the Sacred Hoop was the first and continues to be the largest training and technical assistance provider on domestic assault to tribes throughout Indian Country. The Women’s Health Center is one of the few freestanding abortion clinics remaining in the United States, and is housed in the Building for Women, one of only three such women-owned buildings for women in the United States. New Moon Magazine, the first feminist magazine for girls, has achieved international recognition for its work on behalf of girls.

The Northcountry Women’s Coffeehouse was the longest continuously-running women’s coffeehouse in the country. Women in Construction, which trained and employed women in the building trades, was the first of its kind in the nation. The American Indian Community Housing Organization (AICHO) created one of the first Native-specific shelters in the country, and its urban Indian center, Gimaajii-Mino-Bimaadizimin, is a model for tribes around the country. This is truly a remarkable and vibrant community.

How did you go about collecting all the information for the history?

A few years after the conference, Susana and I invited our colleagues in Women’s Studies to join us in gathering these histories. Several of us collaborated in formulating the book – deciding on the organizations, interview questions, divvying up the work. We initially set out to interview key people at eighteen different feminist organizations, though this eventually narrowed to fifteen and then ten key organizations for the book. Most of us contributed by conducting interviews, though eventually I ended up doing most of the interviewing and writing the book. Overall, we interviewed about a hundred people, and several more than once. We also used materials from organizations’ archives and old news articles. This has been a fourteen-year odyssey from our decision to gather these histories at the conference that day to the publication of this book. It has been a long, but compelling, inspiring, exciting, and incredibly fun ride.

What’s the meaning of the title? Why Making Waves?

When I was trying to come up with the title for the book, I contacted all the UMD Women’s Studies alums on our Facebook page and asked them for suggestions. They were unanimous that the title had to include something about the lake – Lake Superior. Those of who live here know the immense power of the lake to inspire and renew and to connect us. Its spirit is undoubtedly at work in the feminist organizing here. So Making Waves refers to the wonder of Lake Superior. But Making Waves also connects with the way feminist history is referred to as a series of waves – with First Wave feminism happening in the 1800s, Second Wave in the 1960s-1990s, and Third and Fourth Wave representing the contemporary feminist movement. Finally, Making Waves refers to the movers and shakers in this community who joined together, spoke out, and organized to “make waves” — and created lasting and significant change.

What were some of the highlights of writing this book?

The best part of the journey has been interviewing the scores of women and men who were vital to the formation and ongoing thriving of these organizations. What an incredible privilege and honor it has been. I have been able to meet and often become friends with incredible women. They shared their stories with such grace, generosity, and openness. I could easily have spent hours listening to them. Many of the women I interviewed were friends and acquaintances, and this was a chance to learn more about them and, in many cases, to renew relationships. Even if I had not known the women I interviewed previously, these interviews usually felt like conversations between long-lost friends, and on many occasions I felt that by the end of our time, we had indeed become friends. Often, especially when sharing stories of those golden years of feminist organizing in Duluth, it was like being right back in the energy and excitement of those days. Even with people whom I had never met before, we shared a closeness and bonding in memories of that time.

I was consistently humbled by the openness and trust with which the women, many of whom I was meeting for the first time, shared their stories with me. I will always be grateful for this rare privilege.

Some of the most fun interviews I conducted were interviews I did with two or more people at once. Jody Anderson and Fran Kaliher and, in a separate interview, Deb Anderson and Dianna Hunter often finished each other’s sentences in telling me tales of the early days of the Coffeehouse. There was much laughter and good humor. The same was true when I met Marvella Davis and Babette Sandman as they shared their stories of the Women’s Action Group over coffee at Perkins. The way they lit up as they shared their memories of the Women’s Action Group and their evident love and affection for each other and for all the women in the group is one of my fondest moments. The way Patti Larsen and Janis Greene spoke together about Dabinoo’Igan inspired me with their deep commitment to their work, the women, and each other. I was invited to meet with the group of five feminist therapists who had had such an influence on the feminist community in Duluth, and who had continued to gather in their feminist support group once or twice a year for the past thirty-plus years. Their reflections together were tender and wise.

The most fun interview was my group interview with nine women who had worked for CAP [Community Action Program] weatherization. Many of them had not seen each other in years, and what fun it was to witness their reunion. Their fondness for each other was evident as they shared their stories. They clearly had empowered each other in significant ways during those years with CAP weatherization. They hugged and laughed and bounced their stories back and forth. They all had their stories of life-threatening times on ladders that they now recalled with humor. They had created a feminist solidarity when working together that had carried them through their lives.

It was also fascinating to pore over old documents, memos, letters, newsletters, meeting minutes, and newspaper articles. I am so grateful for those who took the time to collect these over the years. I could easily have spent hundreds more hours digging deeply into the treasures in archived material. It reminded me of my first archival work as a young graduate student thirty-five years earlier. My journey seeking out the histories of feminism has come full circle, from my early adventures combing through nineteenth-century archives of some of the earliest feminist thinkers and activists in the United States to those of the present day.

Doing this work has connected me to this community in a whole new way. I am honored to be their storyteller. I love this community. They have enriched my life in countless ways. It is a great honor, privilege, and joy to share their story with the world.

What is your own place in this story?

I moved to Duluth in 1980 at an amazing time, just when so many of these organizations were beginning and feminist energy here was so high. My first couple of years in Duluth were everything I had dreamed of. I trained to be a consciousness-raising facilitator with NOW and led CR groups with Joyce Benson. I was part of the early years of the creation of the displaced homemaker program, Project SOAR, and the political organizing of the Greater Minnesota Women’s Alliance. All the while, I was working with the group developing the Women’s Studies minor, and taught the first Introduction to Women’s Studies class at UMD. I was marching, organizing, researching, teaching – living and breathing feminism. It was a heady time – full of excitement and energy and enthusiasm. Duluth was coming into its feminist awareness and activism at the same time I was. It was the perfect place to be as a budding feminist. The Northcountry Women’s Coffeehouse, which opened in 1981, provided my deepest connections with women’s culture and community in Duluth. I’ve made some of my best friendships, and met the women with whom I’ve been making music in our group, Wild by Nature, for thirty-five years. The women’s music scene was the lifeblood of the feminist community here, and I was fortunate to be in the heart of it. I have also had the great privilege of teaching Women’s Studies students for over thirty-five years. The feminist community in Duluth has been my heart and home for all of my time in Duluth.

Posted byAlison Aten on 18 Aug 2016 | Tagged as: Authors, Interview

In her new book, Tell Me Exactly What Happened, veteran 911 operator Caroline Burau shares her on-the-job experiences at both a single-person call center (complicated by a public walk-up window) and a ground and air ambulance service.

We asked Caroline more about the changes in the 911 dispatch community and the specific challenges dispatchers face.

Meet Caroline at the book launch celebration for Tell Me Exactly What Happened on Thursday, September 8, 2016, at 7:00 pm at Common Good Books in St. Paul.

Your first book, Answering 911: Life in the Hot Seat, details your rookie years as a 911 dispatcher for Ramsey County. How long were you there, and how is Tell Me Exactly What Happened different?

I worked at Ramsey County for two years, then another two years at White Bear Police Department. Tell Me Exactly What Happened starts with my first year at White Bear, and ends after eight years as a medical dispatcher at an ambulance company.

Answering 911 is about the shock and awe I experienced as a rookie dispatcher, and Tell Me Exactly What Happened is about what happens after the awe wears off and what was once shocking becomes routine. It’s about how the things that may make you a great dispatcher may make you a really annoying parent or a distant spouse. It’s about losing people you care about to the job. It’s about losing people you will never meet. It’s also about the people you are sitting next to when these things happen, and how they become like siblings in a strange, macabre, sleep-deprived second family.

And in between those things, it’s also about all the strange new things I or my partners heard on the phone since my first book was written. In ten years, they do pile up.

How has the profession changed in the past several years?

Cell phones have changed things a lot, and not for the better when it comes to 911. It used to be that when a call came in from a traditional “land line,” the dispatcher could see an exact address plus an apartment or suite number. But more and more people are dropping their landlines and only using cell phones. The technology exists to pinpoint a cell caller as accurately as a landline does, but most departments don’t have that technology yet, and their budgets won’t allow it. I actually just visited a 911 center that didn’t even have computer-aided dispatch yet. I couldn’t believe it. The dispatcher wrote all calls, addresses, and every other detail down in a notebook. A notebook.

When I think about change in dispatching, I get stuck more on what needs to change, really. Dispatchers need more and better training. In Minnesota there isn’t even a 911 dispatcher cert course anymore. Most training happens on the job under huge time constraints and is very “catch as catch can.”

I’d also like to see dispatchers get reliable emotional support for what they go through day to day. Because of the culture in emergency services and also because of short-staffing, most dispatchers don’t get any relief after a traumatic call. Someone who has just dispatched an officer-involved shooting scene shouldn’t have to stay in the seat and keep working, for example, but it happens all the time. Dispatchers need the opportunity to step away and talk to someone after a terrible call. And they shouldn’t have to ask for it. It should just be the way things are done.

I probably sound ridiculously biased toward the profession, and I’m not ashamed of that. Dispatchers usually make up a much smaller percentage of any given police department or ambulance company, so they get overlooked. I’d like that to change.

Headlines about 911 dispatchers often bemoan the slow response times or mistakes. What would you like people to know about the job?

Depending on staffing, a dispatcher can be responsible for monitoring multiple radio channels and multiple phone lines at the same time. So, you might hear a recording of a dispatcher on the phone with someone, and it may seem like he or she isn’t listening or doesn’t care. But that is probably not the case at all. It’s just that if you have to listen to several things at once, something has to give. I worked in a single-person dispatch center for two years and felt constantly like I was missing things, and I know that I was. You just compensate by getting better and better at knowing how to triage it all. I had hoped that it would get better in a dispatch center with multiple dispatchers, but it really just meant more work for fewer dispatchers per call.

Basically, if all you heard was a sixty-second recording of the 911 call on the evening news, you’re probably not getting the whole picture.

You write about the toll this kind of high-stress job takes on you and your colleagues, yet so many people stay in the job–why do you think that is?

I think most dispatchers stay on the job because they like it, and they know (even if nobody else does) that a seasoned dispatcher who can multitask like a madman is a truly awesome thing to behold, and that skill and efficiency saves lives.

There are some who stay in the job long after they’ve burned out. Part of the problem is that it’s not a skill set that transfers readily to other careers. When I left dispatching to go into the corporate world, it took me a long time to get used to the idea that a clerical error or a missed phone call from a client could be considered an “emergency.” It took a while to get used to the fact that what I do now is NOT life or death. It will not be on the news, one way or another. Even if you’re miserable, there’s a lot of pride in the idea that as a dispatcher you’re doing something that changes lives. Saves lives. It matters.

What is the difference between a public safety dispatcher and a medical dispatcher?

Public safety dispatchers are usually the first to pick up a given 911 call, so they have to ask for and verify the address of the call and dispatch police and fire if needed. If a 911 call has a medical component, then the public safety dispatcher transfers it to a medical dispatcher, who sends paramedics by ground or by helicopter, and then stays on the line with the caller to give “pre-arrival” instructions. So, they are both 911 dispatchers, just with different roles.

How has the 911 dispatch community reacted to your first book?

Based on the reader reviews I’ve seen, and the followers on my Answering 911 Facebook page, I think half or more of my readers actually are dispatchers. They relate to what I went through as a rookie, and while the details might change a bit from region to region, the basics of the job are very much the same. The feelings are the same. Some dispatchers tell me they make their loved ones read it, so they can feel a little better understood. Some trainers make new dispatchers read it, so they can have some idea of what to expect on the job. This is all a huge honor to me, and humbling. These are the people I needed to do right by with Answering 911, and of course I wanted to do the same in the new memoir.

Do most people understand how incredibly stressful the job is? Is chronic workplace stress a common problem?

I think most people have work stress to some degree or another, and part of me feels selfish writing about dispatcher stress like it’s the only stressful job. But dispatcher stress is unique, and uniquely overlooked, and I don’t think most people quite comprehend it, no. Generally dispatchers are too busy to toot their own horns, so I’m just going to sit over here and toot it for them.

I think what people don’t understand about dispatching is that it’s not all funny and bizarre, and it’s not all murder and rape. In between the notable calls are about a million semi- or non-emergent calls, and those can really grate on you, too, partially because there are just so many and partially because they can get in the way of properly managing the really critical calls.

Another dispatcher stress I address in the book is powerlessness. Shows like CSI make things like detective work and lifesaving look so fast and easy. But most of the calls that come in are for crimes that are already cold and lives that are already lost and can’t be helped. Being a dispatcher often means always doing everything you possibly can, but having to accept that most times everything is not enough.

Posted byAlison Aten on 20 Jul 2016 | Tagged as: African American, Arts, Asian American, Authors, Book Excerpt, Literary, MHS press

Excerpt from David Lawrence Grant’s essay, “People Like Us,”

in A Good Time for the Truth: Race in America, edited by Sun Yung Shin

Minnesota Not-Nice

Anyone who has ever been in a difficult, complicated relationship knows that the opposite of love is not hate. It’s indifference. Neglect is indifference’s twin sister. And there is no such thing as benign neglect. Neglect is, in its truest meaning, a verb. And like twin horsemen of the apocalypse, Neglect and Indifference have teamed up to cause a lot of damage.

The evidence of the damage is everywhere to be seen: failing schools; high concentrations of persistent poverty in failing neighborhoods; the egregious over-incarceration of people of color; an alarming number of annual incidents in which people of color are shot by the police or end up dead in police custody. How did things get so bad, even here?

History Matters

As always, it helps to know the history. Minnesota’s soldiers returned from the Civil War thinking, “Union restored; slavery finished; problem fixed.” The slaves had been freed. Why wasn’t their community exploding with vigor, enthusiasm, and industry, looking to make the most of their newfound liberty? Why were they still having problems? “Why, after all this time, aren’t they becoming more like us?”

Any reader of the fledgling black press during Reconstruction would be mightily impressed at the astonishing degree to which the recently freed slaves were, indeed, deeply grateful . . . were, indeed, working with great vigor, enthusiasm, and industry to build a better life for themselves and their community. But even though two hundred thousand black soldiers had just served bravely and nobly in the cause of Union, they found themselves still excluded from every new opportunity. The promised forty acres and a mule were never delivered. White veterans in the tens of thousands got an opportunity to help this nation-building effort in the underpopulated West—in places like Kansas, Nebraska, and Oklahoma—along with an opportunity to build a personal legacy of prosperity that they could hand down to future generations. Black veterans got . . . lectures about “bootstraps” and hard work—something about which they already knew plenty.

There would be no help forthcoming, no assistance in lifting themselves out of abject poverty and the shadow-world of life on the extreme margins as second-class citizens. Instead, there were Black Codes (spelling out where black people could go and could not go; requiring annual and unbreakable labor contracts; demanding fees from any who worked in any occupation besides farmer and servant) and Jim Crow domestic terrorism. Now that slavery was gone, what black people encountered was the cold reality that the rest of America still seems so completely unready to admit: that America’s real original sin was not slavery, but white supremacy. The law may say Jim Crow is dead . . . but if it is, then it’s having a long and vigorous afterlife.

I was doing some neighborhood organizing work in Chicago during the summer of 1970. When I told a friend there that I was getting ready to come live in Minneapolis for awhile, he said, “Aw, brother, really? Why? Worst cops in the whole world up there, man!”

I used to volunteer at a residential substance abuse program in South Minneapolis. After finishing my last tutoring session one evening, I started walking home about 7:30 pm. Just as I crossed the street, a car came tearing up at high speed, and three plainclothes police officers leaped out with guns in hand. They identified themselves, and then one of them holstered his gun, threw me up against the trunk of the car, and cuffed me.

I asked why. One of the officers pulled a handgun from his boot—a personal, non-regulation weapon—held it against my head, removed the safety, and cocked it. That’s a helluva sound—a gun being cocked while jammed tightly against the dome of your skull. Intimidating. I was intimidated. But more than anything, I was angry. And it occurred to me, even in the heat of the moment, that this was exactly the reaction he wanted . . . like someone who lights a fire and thinks, Now, let me throw a little gasoline on there. Instead of answering my question, the cowboy with the gun to my head told me not to move, then shoved my head hard to one side with the barrel and said, “Wouldn’t even breathe real hard if I was you. This gun’s got a hair trigger.” There was another reason to be wary of that gun. I knew countless stories of weapons like that, produced from a boot or the small of an officer’s back, meant to be placed in a suspect’s hand or close to his body should he somehow end up dead by the time the encounter was over.

One of the other officers finally spoke up: “Liquor store was robbed a couple blocks away about twenty minutes ago by somebody who matches your description.” As they inspected my ID and the other contents of my wallet, I told him as calmly as I could that right across the street, there was a whole building full of people who could vouch for who I was and where I’d been all evening. All three cops heard this, but they ignored it. It was as if I hadn’t said anything at all.

They threw me into the back of their car and radioed that they’d arrested a suspect. As they began to pull away from the curb, a voice on their radio told them to stay put. A lieutenant pulled up in a plain car behind us and talked with the officers while I listened to the police chatter coming over the airwaves.

The suspect was described as a light-skinned black male, about five foot seven, with extremely close-cropped hair and a slight mustache, wearing a knee-length, light tan leather coat. That was the only time I gave them attitude. I smirked a little and asked them, “That supposed to be me?” I stood about five foot ten in my boots, and I’m a medium brown . . . not someone that anybody has ever described as “light-skinned.” I wear glasses and was then sporting a scraggly goatee. And at that time, I had what might have been the biggest, baddest Afro in the entire state of Minnesota—a foot-tall brain-cloud kind of Afro, as far from “close-cropped” as it’s possible for hair to get. And I was wearing a waist-length, almost sepia leather coat, nothing remotely like the one in the description.

The lieutenant heard this, too. He flashed his badge at me and said to them, “Guys . . . really? Cut this guy loose.” Just like that. One of them spit, a couple of them grumbled, they uncuffed me and pulled me back out of their car, returned my wallet, and then tore off back down the street. No, “Oh, well, sorry, sir,” from them. Nothing.

I knew, as I tried to shake it off while walking home, that other scenes like this were playing out that evening in any number of other places in America. What if that non-regulation gun the cowboy cop had pressed against my head really did have a hair trigger? If I had reacted angrily and resisted, I might well have been killed, as have so many others before me and since, in just such an encounter.

There’s a history to encounters like these. And if you understand this history, even a little, you understand that all the hue and cry about “weeding a few bad apples” out of police departments and doing some retraining will not fix our problem. It is important to weed “bad apples” like that cowboy out of our police departments. But the core of the problem is that although undeniable racial progress has been made, the large numbers of African Americans left behind in intractable poverty are still stuck in the same cultural space as our ancestors were when just newly freed from slavery: stuck on the margins as perpetual outsiders in the land of their birth; feared; stigmatized as criminal by nature. This mostly subterranean attitude applies, in general, to other low-income communities of color as well.

So, the hard truth is that police departments deal with communities of color in exactly the way that American society, Minnesota society, has asked them to. There’s a readily observable pattern: people who find themselves routinely locked out of equal opportunity will generally find themselves locked up to roughly that same degree. Racially based restrictive housing covenants were declared unconstitutional in 1948, but they have continued in practice. Until 1972, thousands of municipalities had vagrancy laws on the books that were about regulating black people’s lives. Even though those laws have long since been struck down, the racist beliefs that created and sustained them are still very much around—and as a consequence, too many police officers sometimes behave as though they’re still on the books. The result is that simply being young and black or brown is a de facto “status crime.” It’s not necessary to do anything wrong . . . just step outside on the street or get behind the wheel of your car, and you could already be in trouble.

Listen

As many black families pulled up stakes and left the communities where they’d been born and raised, searching for a better life, this part of the collective African American story never seemed to be grasped by the communities to which they moved, Minnesota included. Truly welcoming weary strangers into your company means, first, learning something about their story. How else can you possibly begin to divine what assistance or support they might need from you as they begin to build a new life? But Minnesotans, like other Americans, have seldom known or, seemingly, haven’t cared to know much about the stories of the non-European populations with whom they share this land.

Minnesotans evince little knowledge of the history of settler aggression or the widespread and egregious abrogation of treaty rights when it comes to the experiences of Indigenous peoples native to this soil. There is precious little understanding of the diverse histories of our Chicano/Latino populations, many of whom long ago became citizens, not because they crossed international borders to get here, but because the U.S. border crossed over them as a result of the massive amount of land seized from Mexico at the end of the Mexican War. A story that can be told in easily graspable, shorthand form (think Hmong refugees whose men had helped the U.S. war effort in Southeast Asia, forced to flee their old homeland to escape reprisals) stirs sympathy enough to mobilize an organized resettlement effort. But even that only goes so far. There is little patience here for immigrants from anywhere—Asian and Pacific Islander, African, Latino—or even Americans from much closer to home, like Chicago, who seem slow to assimilate. Ojibwe and Dakota people get the same treatment. And there’s a stark, simple equation at work here: if you fail to value a people’s stories, you fail to value them.

In sharp contrast to this, new immigrants are always listening for and trying to make sense of the stories of their adopted land. But here in the North Country, immigrants scramble to figure out for themselves the many unspoken rules about how to live in harmony with Minnesota Nice. And some of these rules are damned hard. They learn that no matter how angry and aggrieved you may feel, given the history of what’s happened to you and your people, you’re still expected to abide by the unspoken mandate to “kwitchurbeliakin.” That’s “Quit Your Belly Achin’,” for the uninitiated. Because life is just not fair. Period. So, whatever’s happened to you, suck it up and move on. It’s not okay to outwardly show anger or resentment in any way. This is evidence of weakness. And it’s not nice.

Being a true Minnesotan also means being self-sufficient. All cultures express this value in some way, but Minnesota’s is the most extreme iteration I’ve ever encountered. My introduction to at least one man’s version of this ideal came from a mechanic named Bud. He owned and ran a car-repair shop in a South Minneapolis neighborhood that, over decades, he’d seen transition from mostly white, mixed middle and working class, to largely working class and poor people of color.

In an area that had become about 60 percent black, and whose population had been steadily getting younger, the only customers ever seen coming or going were white men over forty. In inner-city neighborhoods of color, places like that become unofficially recognized as “no go zones.” Doesn’t look like your business is welcome there, so . . . you simply erase them from your mental map of the neighborhood, to the extent that when you pass by, you literally don’t even see them anymore. But on the day Bud and I met, the family car was giving me big trouble and I happened to be just a block or two from his place, so I figured it was a good day to stop in and take my chances.

Word was that the guy was racist, but after a little conversation, it didn’t feel that way to me. The more we talked, the more it occurred to me that, really, Bud was just generally a grumpy old bastard . . . and that he probably tended to instantly distrust and dismiss anybody who found it hard to deal with this fact. As I look back on our encounter from the perspective of someone who’s become a grumpy old bastard himself, I’m even more convinced of this. I told him what the car was doing, but he cut me off, grunting his diagnosis before I could even finish. “Alternator. Ain’t got time for that today . . . but I got one I could sell ya.” When I told him that I’d never replaced one and wouldn’t know where to begin—told him I’d just go on and walk home if he thought he’d have time to fix it for me the next day—he shot me a searing look of pity mixed with disgust and said, simply, A man ought never pay another man to do something he could do for himself.

This pronouncement felt stunningly sharp and severe, especially coming from the mouth of someone who did, after all, make his living from doing the repairs that his customers didn’t care to do. His words made me wonder what he must think of most of us men walking around his rapidly changing neighborhood, black and brown men, none of whom had come up, as he did, on a hardscrabble farm established by Norwegian immigrant grandparents who made the clothes they wore and who ate, almost entirely, only the food they grew themselves. People for whom life was hard . . . but who never complained. I thought about us black men from the neighborhood who walk around looking sullen and sad, and how men like Bud must look at us and wonder why. They don’t see much, if any, evidence of the discrimination that keeps us angry and on edge. They certainly don’t see how they’ve ever personally been guilty of committing an act of discrimination against us or anyone else. We don’t “get” each other. They don’t tend to understand much about how the world looks to us, and we don’t tend to understand much about how the world looks to them. So, even though some of the time we share the same space, we avoid talking . . . and when we must, we keep it superficial, allowing ourselves to come tantalizingly close for an instant, but then spiraling past each other like separate galaxies, each on its own axis, into the void.

As Bud’s words sank in, I turned to leave, but then suddenly, something in me wouldn’t let me leave on that note. I felt the need to challenge him, surprise him, through a small, spontaneous gesture, aimed at bridging that yawning, silent gulf between us, if only for a moment. “Okay, then,” I said. “Wanna take a minute or two and show me how to do it myself?” Without needing even a moment to think about it, he surprised me by pulling out the tools I’d need and agreeably talking me through the job while he sipped strong coffee and went back to working on the car he’d been fixing when I walked in.

As we worked side by side in his tiny shop, I eased into a story about my own people—how generations of my folk struggled, always managing to creatively “make a way from no way.” He didn’t say much. But he was listening. My attempt to paint as vivid a picture for him as I could of the people I come from—people who also took what life threw their way and didn’t complain—seemed to resonate with him. Mid-job, I noticed there was a sign on the wall stating that it was illegal for customers to be back there in the shop, an edict he’d apparently decided to ignore in my case. Even though he stepped in to help me replace and tighten the belts, he also decided to completely ignore the sign that said, “Shop Charge, $45 hr.,” because when I pulled out my checkbook to pay for the parts and asked why I shouldn’t pay him at least enough to split the difference on time with him, he said, “Well . . . why? Done it yourself, din’t ya?”

Minnesota Nice can be really nice. Interesting and complicated too.

Bridging the gulf between us is hard. It takes courage and effort. And the effort often results in an encounter that can be both unrewarding and unpleasant. But what alternative do we have? The demographic makeup of Minnesota, like the rest of the country is changing rapidly and radically. By 2050, the majority of America’s citizens will be comprised of groups who used to be called “minorities.” The majority here in Minnesota is likely to remain white for some time, but populations of color, especially the Latino population, will see a dramatic increase. The Somali population of the state was already so large by the year 2000 that Islam quietly supplanted Judaism as the state’s second most prominent religious faith.

As we move forward, we can lean on this: that although it tends to happen slowly and only with great, conscious effort, people and cultures do change in response to the changing realities and needs of their times. If we are to sort ourselves out and make good lives for ourselves in this ever-more-multicultural landscape, we’ve got to start by talking less and listening more.

We can listen—really listen—to one another’s stories and learn from them. Collectively, we can learn to tell a story that includes all our stories . . . fashion a mosaic-like group portrait from those stories that we all can agree truly does resemble people like us.

David Lawrence Grant has written drama for the stage, film, and television, as well as fiction and memoir. He has written major reports on racial bias in the justice system for the Minnesota Supreme Court and on racial disparities in the health care system for the Minnesota legislature. He teaches screenwriting at Independent Filmmaker Project/Minnesota.

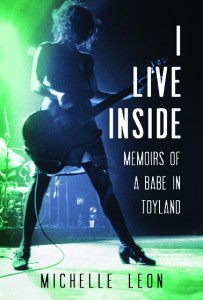

Posted byAlison Aten on 11 May 2016 | Tagged as: Authors, Interview, Music

Michelle Leon was the bass player for the influential punk band Babes in Toyland from 1987 to 1992, and again in 1997. In her new memoir, I Live Inside: Memoirs of a Babe in Toyland, she takes readers on the roller coaster ride of the rock-and-roll lifestyle and her own journey of self-discovery.

Michelle Leon was the bass player for the influential punk band Babes in Toyland from 1987 to 1992, and again in 1997. In her new memoir, I Live Inside: Memoirs of a Babe in Toyland, she takes readers on the roller coaster ride of the rock-and-roll lifestyle and her own journey of self-discovery.

Meet Michelle on Thursday, May 26, at Moon Palace Books. I Live Inside is their Rock n Roll Book Club pick for May!

We asked Michelle to tell us more about how and why she came to write I Live Inside.

I Live Inside documents the five years you spent in Babes in Toyland, but also flashes back to your childhood. Why did you decide to incorporate these vignettes from your youth?

I wrote the book very non-linearly. I was all over the place, creating scenes as they came to me, bouncing from childhood to the present day and back to the Babes days. As I looked through the pieces later, there were so many parallels—family road trips in a station wagon and touring in a van with the band; feeling out of place as a kid and again later as a young adult; moments of loss. So it was very fun to play with that, refining the scenes so they were even more echoing and reflective of each other.

Your prose is so sensitive and sensory and your style poetic. What were your literary influences?

Flannery O’Connor, Joyce Carol Oates, Tennessee Williams, Lydia Davis, Mark Doty, Joan Didion, Amy Hempel. I love the Widow Basquiat by Jennifer Clement; her style of writing in vignettes was something my adviser at Goddard, Douglas Martin, showed me when he saw how I was writing my book, and it gave me confidence working in that style. Patti Smith, Eileen Myles. Darcey Steinke’s new book Sister Golden Hair is killer; she was also an adviser at Goddard. Anything Maggie Nelson, but especially Bluets—more vignettes. Half a Life by Darin Strauss is another. The Seal Wife by Kathryn Harrison. Mary Karr’s Cherry. I read tons of memoirs preparing for this book. I definitely have a literary comfort zone—I should branch out.

Why did you want to share your story?

I didn’t want to share it at first. I was very protective and defensive about the subject for a long time; I felt a lot of sadness and loss. I didn’t want my identity to revolve around being the former bass player in Babes in Toyland. But people always asked me what it was like being in the band. I never had the answer they wanted, like I was supposed to tell stories about trashing dressing rooms and throwing TVs out hotel windows and hanging out with Bono. What I had was a very complicated and intense relationship with two other women that was like a marriage, while running a business together, living together, creating art together, experiencing the highest of highs and navigating horrific loss together. Loving each other like a family, driving each other crazy with our weird habits and egos, the unique bond of making and playing music together; these beautiful and singular life experiences we shared, and it still not being enough to keep us together. The day came when I HAD to write this story as a way to understand it all.

What do you miss most about being in the band?

I miss the energy of playing music onstage, the elation in that, the freedom; not knowing what town you are in when you are touring, not brushing your hair or going to Target for toilet paper. Living in that weird alternative universe. I miss co-writing songs and drinking beer at practice, having inside jokes and laughing my ass off with my band. I miss going to music stores and trying out new distortion pedals and strings and guitars. I miss having a job where a pair of American flag bell-bottoms is the perfect thing to wear. I miss traveling to places I never dreamed in my life I would see. I miss making new friends and seeing old friends out on the road.

But I am someone who loves home, loves staying in and being quiet; being in a touring band is very challenging for me. I don’t like being away from my family, friends, pets, kitchen, bed, bathtub, garden, neighborhood, and lovely old home, even though there are so many things I love about being in a band.

Do you still play the bass?

A little bit. My step-kid, Jae, goes to a performing arts high school, and I just went to the school and played with Jae’s classmates. We played “Smoke on the Water” together and it was awesome. Jae plays my old bass—a 1975 Fender Jazz we call “Lionheart,” a combination of our last names—and that makes me very proud.

What is your relationship with the band like now?

We have always remained close friends through so many different phases of life. Not that it was always easy. There was a lot of healing that occurred over the years. Still, I was really scared about how they were going to react to the book. It is such a personal story and a serious invasion of their privacy. So I have been overwhelmed and moved by their support. Lori was amazing at helping me remember details; she has an incredible memory. I’d text her questions like, “Have I ever been to Belgium?” And she’d know the answer. The experience of writing this text has brought us closer, which was a beautiful surprise.

What have you been up to since your departure from the band?

Everything! I worked at a flower shop, owned a flower shop, lived for almost a decade in New Orleans, where I renovated old houses and worked as a real estate agent, stayed for a year after Katrina. I finished college and grad school, then also earned my teaching license. I work as an elementary school special education teacher, with an emphasis on autism spectrum disorders. I married an amazing man a few years ago, gave birth to our son River the week after my forty-sixth birthday, and help co-parent Jae. We have three crazy, sweet dogs—two are therapy-certified and come to school with me. I am very blessed in this life. I am ready for more.

Posted byAlison Aten on 28 Apr 2016 | Tagged as: Authors, Event

We’re excited to be a sponsor of this year’s Twin Cities Independent Bookstores Passport!

This Saturday, April 30 is the Second Annual Independent Bookstore Day, and to celebrate, ten Twin Cities area bookstores have teamed up to produce a Bookstore Day Passport.

As noted on the Midwest Independent Booksellers Association website:

Customers pick up a copy of the passport at any of the participating stores and receive their first stamp. Any individual who travels to all ten stores during business hours on Independent Bookstore Day and receives a stamp from each store will receive a $10 gift card from every participating bookstore–$100 in total value. When all the stamps have been collected, customers snap a photo of their completed stamp page and send it to the Midwest Independent Booksellers Association via twitter (@MidwestBooks), and we will gather contact info and send them their gift cards.

Moon Palace Books in South Minneapolis will also be producing a new and updated edition of its Twin Cities Bookstore Map, which will include all bookstores in the Twin Cities, not just those participating in the passport, Independent Bookstore Day, or members of MIBA.

We’re also honored to have several of our authors participate in Independent Bookstore Day activities:

Birchbark Books at Noon

Heid E. Erdrich signs and shares her book, Original Local: Indigenous Foods, Stories and Recipes from the Upper Midwest

Common Good Books from 2:00-3:30 pm

Sun Yung Shin and IBé sign A Good Time for the Truth: Race in Minnesota

Magers & Quinn at 7:00 pm

Michelle Leon reads and signs her new book, I Live Inside: Memoirs of a Babe in Toyland